Family-Friendly Multifamily

Learning from strollers to design better family-friendly buildings.

While my wife, Ksenia, and I were expecting our son, Leny, I, as a stereotypical father-to-be, immersed myself in stroller reviews and was immediately amazed by the ingenuity of their designs. Brands consider all the little nuances in a baby's and parents' life and come up with sophisticated solutions: modular systems that evolve as a child grows, one-hand folds, countless safety features, and accessories. I even found a stroller that compensated for the lack of space in our one-bedroom New York City apartment by folding flat with a bassinet attached.

Naturally, this got me thinking about ways we could learn from these products to improve apartment design for families, in particular:

How could we make the design of family apartments more opinionated?

How can homes better respond to children's developmental needs?

How can interiors evolve as children grow?

How can we plan for things that break along the way?

How can we design for children in a way that also looks good to adults?

We need opinionated design of family friendly apartment buildings

The subject of family-oriented apartments is gaining more attention in the North American real estate development community. However, family-focused residences still constitute a small portion of new construction.

In “Fighting The Childless City”, Brad Hargreaves points to the lack of family-friendly projects as a result of developers hedging their bets:

While shifting demographics may provide a tailwind for family-sized apartments, some developers and analysts point to a different problem at the root of those units’ poor historical performance: their design.

Specifically, larger “family-sized” units in urban developments are often designed to solve for the needs of roommates and families simultaneously. It goes without saying that those two demographics have very different preferences, and it’s difficult to satisfy both use cases with a single unit.

Specifically, roommate- and family-oriented units have a few key differences: family-oriented units have more, smaller bedrooms, and windowless bedrooms / dens are appropriate; family-oriented units don’t need a 1:1 bedroom:bathroom ratio and have baths rather than showers in the secondary bedrooms.

In order to de-risk a project, many developers choose to create a product that could, in theory, cater to various clients. Unfortunately, the desire to please different people often results in none being truly satisfied. As Bobby Fijan, a developer working on family-friendly apartment buildings, observed: “For most apartments, certainly in the United States, the objective is to offend as few people as possible.”

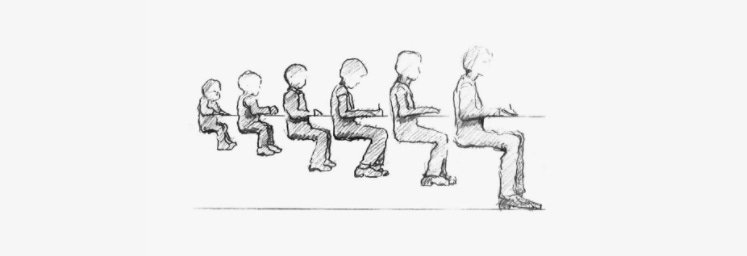

Designing family-oriented apartments with the same attention to detail and usability as stroller manufacturers would require an opinionated and product-led approach to development. Instead of planning for a common denominator across all potential renters, we would need to think about the unique needs of parents and children of different ages: from infancy to teenage years — and design accordingly.

Montessori apartments

Many educational spaces, such as kindergartens, nurseries, schools, museums, and playgrounds are nothing short of opinionated. They are designed to be more inspiring, safe, and conducive to children's development.

Yet when the kids return home from these well-crafted places, they often find themselves in relatively unprepared surroundings. Ashley Yeh, the author of "The Montessori Home", argues that:

Our children often find themselves at odds with a traditional home environment, as the physical space is usually designed with adult proportions in mind. You must learn to see your child’s environment with fresh eyes, from their perspective, so that you are more effectively able to create simple, organized, and beautiful spaces that invite more meaningful learning and offer natural opportunities for independence.

The artificial separation between a well-designed "educational" space and a home is confusing at best, and harmful at worst. Many modern educational spaces have been modeled on the principles developed by Italian pedagogue Dr. Maria Montessori. Her research investigated the impact of the built environment on children's healthy development from birth. Dr. Montessori showed that kids are always hard at work in absorbing their environment, learning patterns from it, and training themselves to become self-reliant in society and the world. As a result, a prepared environment is essential for a child to develop their autonomy, self-esteem, and self-confidence.

It is striking that we don't commonly apply these design principles at home, where the kids spend the most time. In particular, by improving accessibility of apartments so that children can interact with the space without the intervention of an adult. The space should be designed with kid-sized objects from ordinary life like sinks, furniture, brooms, that can be easily accessible.

We don't expect parents to hack together a stroller from Home Depot parts. Yet we expect them to figure our how to fit out their home for children completely on their own. This creates an opportunity for developers and architects to propose a better design that would incorporate pedagogical best-practices and recommendations by default.

An environment that can evolve over time as children grow

Norwegian designer Peter Opsvik couldn't find a suitable chair for his young son that could accommodate him at the table. His son had already outgrown his highchair, yet the adult products were still too big for him. Opsvik set out to design a chair that would change at the pace of his son's growth. He succeeded and created what later became a legend of industrial design – a reconfigurable chair called Tripp Trapp.

In a similar fashion, an apartment designed for families with children should be able to adapt as they grow and their bodies, abilities, and needs change. Instead of buying and cycling through furniture of different sizes, a rental product can natively integrate reconfigurable elements within the apartment.

It can be achieved with something as simple as modular shelving that can be rearranged over time. Or something as complex as integrated bunk bed systems, robotic furniture, and flexible plumbing fixtures that can change their height.

For renters, making such improvements on their own may be prohibitively costly. Unlike homeowners, they may expect to move and not be able to recoup some of that expense in time. By contrast, long-term multifamily owners can amortize such an investment across several tenants.

A higher operating income may justify making apartments reconfigurable over time. It could offset larger upfront costs and operational complexity for property managers.

For when things break along the way

Some developers, design-oriented hoteliers, and property managers are afraid of the occasional mess that can come with children in a space. Play, experimentation, and creativity may not always bode well with beige couches, white walls, and a "pristine" space designed for adults. There's a good reason you don't see too many white strollers.

The design of a family-friendly apartment building must proactively take maintenance into account. It may mean borrowing from the hospitality playbook with robust and easy-to-clean materials or prioritizing laundry rooms over walk-in closets.

We can also imagine more radical experiments like completely modular walls that allow for easy replacement of some parts or sections. Imagine having the lower half of the wall become a dry-erase board for a few years, then switching back to normal drywall. Modular wall systems (like LADA Cube etc) already enable various skins to be clipped on them in seconds.

Ultimately, design with maintenance in mind may not require more expensive solutions. It's just got to be an integral part of the design brief that a development project optimizes for from the beginning.

Balancing design for children with a tasteful environment for adults

One of the problems with real estate projects catering to families is that they quickly become too whimsical: with playful wallpapers, patterns, and extremely vivid colors everywhere. They end up looking so tacky that they no longer feel like a place an adult would choose to live in on their own.

Family-friendly apartments should have an environment that is subtly convenient for kids of different ages, yet looks completely normal to an adult (with or without children).

One of my favorite examples of that approach is illustrated by the French landscape architecture firm BASE known for their extraordinary playground designs. Their projects look like standalone art installations.

Similarly, design for child safety only looks bad when it is done as an afterthought, like a bandaid on otherwise pristine spaces. If it becomes an integral part of the design process — it may result in beautiful environments that don't have any obvious visual cues of being designed for safety. For instance, a floor-to-ceiling net can both protect children from falling over and look like a sophisticated architectural element unrelated to safety.

There're myriad other product improvements that we can think of in designing better apartments for parents and their children alike. From creating communal amenities and shared services to making childcare a bit easier and affordable, designing spaces for sound sleep, and many more. It would require experimentation to get to the right mix of features, services, costs, and their appearance.

At the same time, we have to be mindful of over-amenitization that may feel too gimmicky. The apartment should always remain a canvas for living rather than a rigid "machine" dictating ones lifestyle.

It’s time to play

This theoretical inquiry became very tangible when Ksenia, Leny, and I moved from New York to Los Angeles. Our search for a new family-friendly home has been taking much longer than we anticipated. I was always rather picky about apartments, but now I’ve suddenly started caring about bathtub heights, entry storage space, stairs, and access, light and open space, floor materials, heating and water quality, etc.

It reminded me that while I was browsing stroller reviews, I couldn't help but notice the sheer passion of parents for products that made their families lives easier. Whoever figures out how to help people feel the same way about apartments - will undoubtedly do well.

Further reading and listening

“The Montessori Home” by Ashley Yeh

“Why We Don’t Build More Apartments for Families“ by OddLots Podcast

“Why we can’t build family-sized apartments in North America” by Center for Building in North America

“Miniature Architecture” by ArchDaily

Thanks for this post and for the book recommendations! I had my first kid a few months back and designing a home fit for her and us is top fo mind for us.

So much of "modern" multifamily architecture seems to tend to push families further out of cities. Architectural adaptation is something that isn't really possible within a generation or 2 like it is in SFD. What are some solutions that allow for these buildings that attract young couples to grow with them instead of push them out?