Movie Credits for Buildings

One building — many names.

My name is Fed, and I write about creative direction in real estate. Currently, I lead product strategy, brand, and marketing at Neutral, a wellness-oriented multifamily developer operating in the Midwest and California.

Every building needs its "movie credits."

Brady Corbet, the director of "The Brutalist" said: "Every time we make a film we start a new company, raise funds, hire 250 people, and repeat the process every 18 months."

The resemblance to real estate development is striking. For every new building, developers create a new company, fundraise, hire hundreds of people across various consulting and construction trades... This process is repeated time and time again, often with new people involved in every project. And yet, can you easily identify individuals who were involved in the construction of a specific building? — I can't.

Our fascination with star architects makes some buildings commonly known as “Zaha’s museum”, “BIG’s tower”, or “Heatherwick’s blob”.

Frank Lloyd Wright took this to an extreme by creating a signature tile for select projects that he deemed to be fully realized according to his vision and specifications.

In real estate investment circles, the buildings are commonly known by the developer's name: a "Related tower", "Lennar home", or "Caruso mall."

That focus on the lead designer or developer is not dissimilar from cinema's fascination with a specific director or studio: a "Tarantino film", a "Marvel movie."

The difference is that along with highlighting the leading names, each of these large movie productions ends with credits that list every individual involved. There's simply nothing equivalent in the building industry.

Buildings take a long time. Years, sometimes decades. People who played an integral role in the early days may move on. They shouldn't be forgotten. Also, individuals can play many discrete roles within the same project. They should be credited for these various contributions. Every name counts. From the banker who signed the loan to the trucker who hauled the timber.

Movie credits are a recent phenomenon

It's easy to discredit the idea of full building credits because our industries are different. Surprisingly, full movie credits are a rather novel phenomenon.

Classic movies had barely any credits at all. Some featured opening credits lasting no longer than a few minutes with no closing credits. During this period, only a few key people were mentioned, at best.

By the 1940s, some notable films like "Citizen Kane" and "The Wizard of Oz" pioneered extensive end credits. Still, these were personal choices by individual directors and studios, not an industry-wide practice.

Only by the 70s did the now-familiar end credit format become prevalent. Driven, in part, by labor unions. Credits often come with strict hierarchy and contractual requirements dictated by the Directors Guild of America (DGA), Writers Guild of America (WGA), and Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA), among others.

Today, blockbuster movie credits can run for tens of minutes on end.

Building precentents

Although full building credits are uncommon, many individual practices in architecture, development, and finance do highlight the contributions of team members on specific projects. Unfortunately, this information is scattered and isolated across different firms.

Recently, I ranted about the lack of long form crediting in the real estate industry to Kuba Snopek. He listened patiently and said, “You know I created a project with full building credits, right?”

In 2017, Kuba co-directed a crowdsourced project for an abandoned site in a public park in Dnipro, Ukraine. The outcome was a multifunctional cultural installation Stage, co-designed, co-constructed, and co-funded by an international and local community of designers, builders, and donors.

As he explained, the project’s nonprofit and collaborative nature made full credits essential. For many participants, having their name commemorated was an important motivation to see the project through with no other compensation.

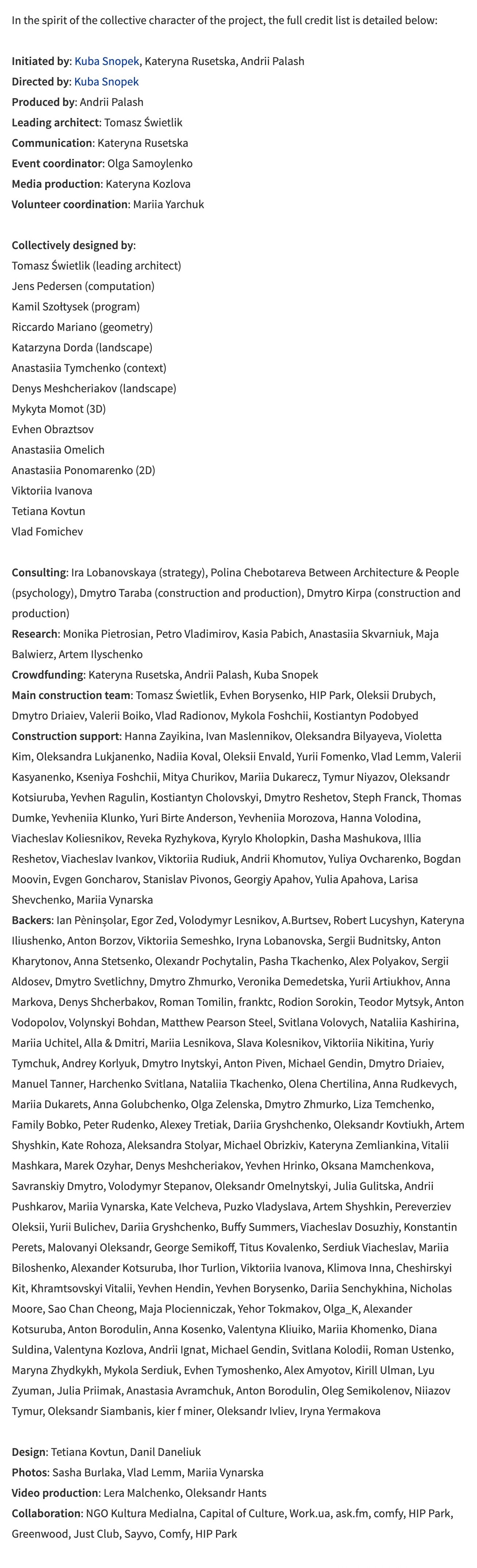

When the project won an ArchDaily award, the team insisted that every single contributor be listed on the website. Below is a screenshot of these credits.

This is by no means a short list, and you might expect it to be a massive structure. In reality, the building is a rather modest outdoor pavilion.

I’m not saying this to diminish the complexity of the project, but to illustrate that even something that seems deceptively small required a whole “village” to bring it to life. Now imagine what full credits for a skyscraper might look like.

Keeping records

The challenge of tracking building credits often comes up in my day-to-day work in development. When we publish our projects, we always aim to list the full project team.

Often, we end up listing organizations rather than individual contributors. Even if we wanted to include everyone, there is no straightforward way to collect and reconcile the full list of people involved across all consultants, subcontractors, and suppliers.

Implementing "movie credits for buildings" would require proactive intent and some kind of digital repository specifically designed for tracking since a project's inception.

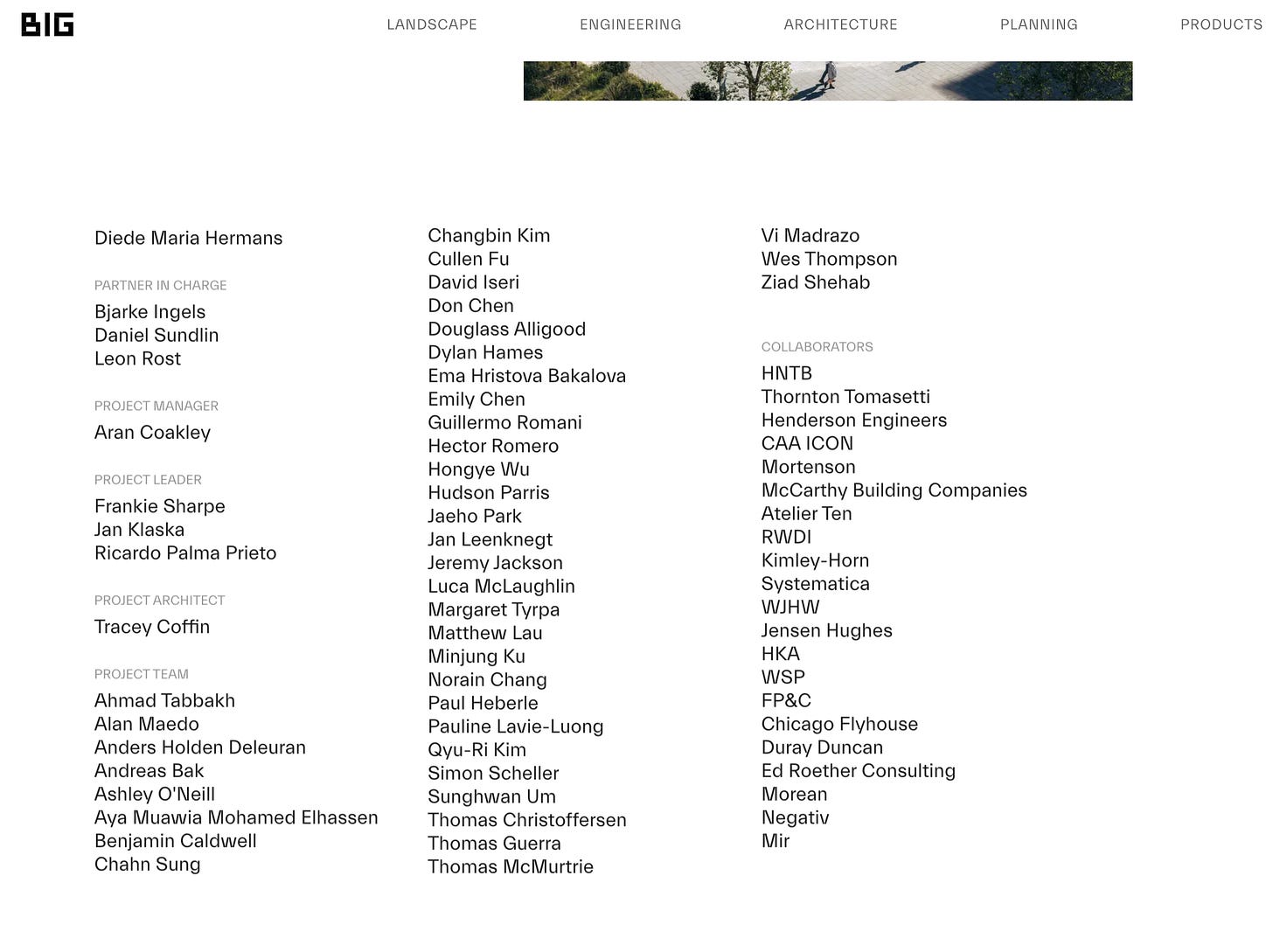

For example, architecture office BIG uses accounting time sheets to track every individual on the team who contributed to a given project, and that automatically generates the project credits.

The film industry has digital platforms like IMDB that track all individual credits and make them easily discoverable. Unlike LinkedIn, which tracks employment in organizations, IMDB is structured around specific projects.

There's no direct equivalent to IMDB in the building industry, no scalable platform tracking building credits at the individual level. The closest would be ArchDaily, Architizer, and ProCore Construction Network. These platforms are limited and focused primarily on capturing credits at the level of firms (i.e., ArchDaily, ProCore) or building products (Architizer).

That said, I'm not concerned about software. The tools will come once the demand is there.

The first step is for us to collectively agree that full building credits should become a universal practice across our industry within ten years.

Of all the players in the building industry, real estate developers are the ones with the most comprehensive information and control to lead the way. Let's make it happen.

Best,

Fed

Thank you for reading. You can support this publication by subscribing, sharing this article, or booking a consultation with me.

And like in movies you want to work with Tarantino’s director of photography or lighting person, and so on. The credits of the project are also a graph of trust. If you want to find a good acoustic engineer or MEP consultant, it is better to see who is working with who and making what. Some platforms have tried to map it. When I was at ArchDaily we structured this information under this thesis, and that actually could be valuable for consultants and other collaborators. Because they market their services to architects.

There was a thought, probably by Paul Graham, that recognition or prestige is a form of reward where other rewards are lacking. So when I see credits and prestige I better start running away!