Case Study Houses 2.0.

It's a good time to reboot the program for XXI century.

The United States has been building around 1 million new single-family homes per year. The Case Study Houses program produced 25 homes over a span of two decades.

And yet, on coffee tables around the world, you're likely to stumble upon one of many books covering the Case Study Houses.

Despite the program being close to a century old and rather humble in its scale, it has managed to achieve a disproportionate, seemingly ubiquitous presence and serve as inspiration for generations of designers and homeowners.

In this letter, we'll take a brief look at the history of the Case Study Houses program, speculate on the reasons for its lasting success, explore relevant modern precedents, and sketch out a concept for its potential reboot.

The program

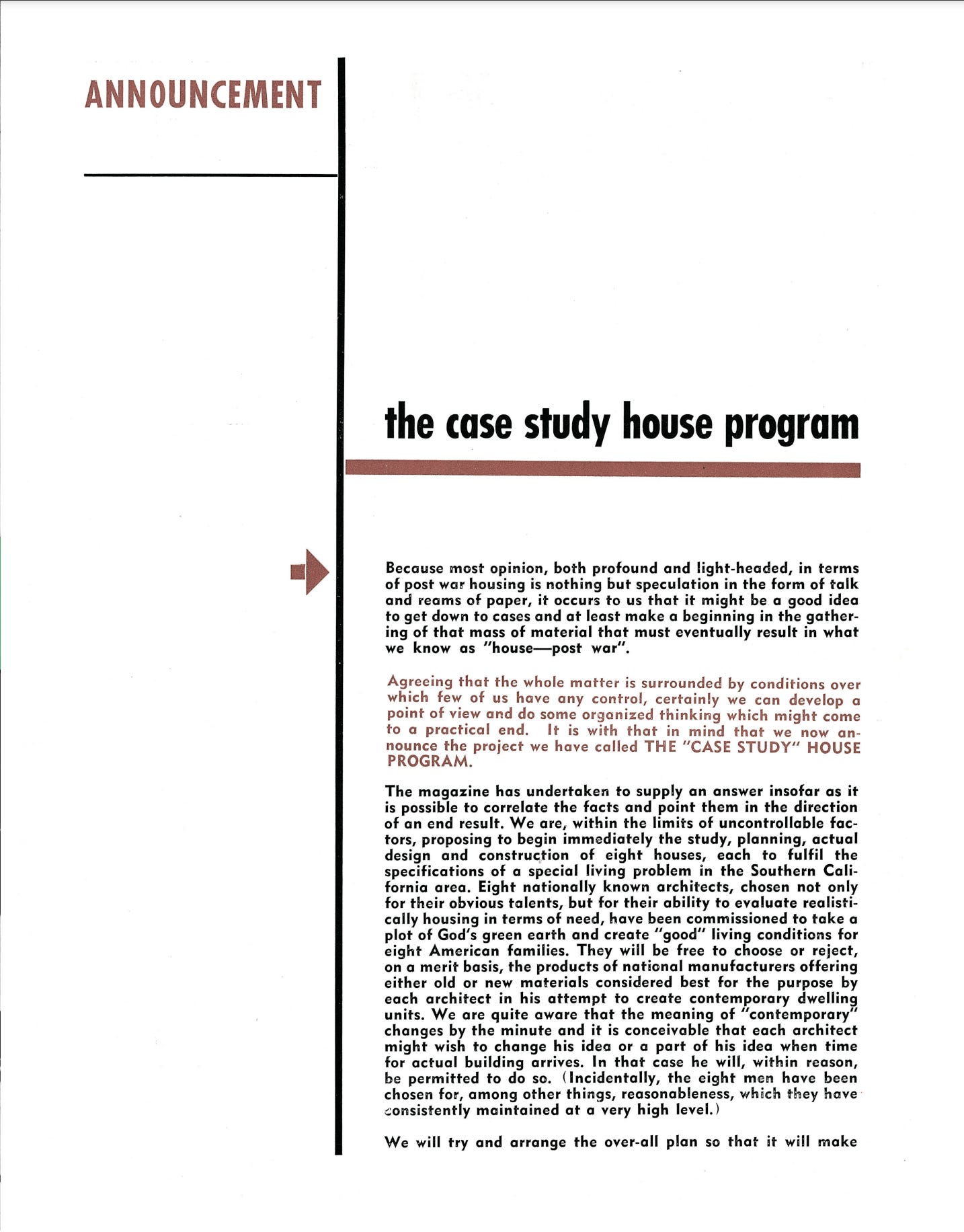

The Case Study House program invited select architects to design and build homes in post-war America. It lasted from 1945 to 1966, during which a total of 36 homes were designed by renowned architects of the time, with 25 of them actually being built.

What makes this program unique is that it was not a government-sponsored initiative, an individual’s philanthropic endeavor, or even a paper architecture competition. It was a privately funded program by an architectural magazine — Arts & Architecture. This media outlet funded both the design and construction of actual innovative homes, then published and open-sourced the results.

In reflecting on the program's resilience, we can identify five primary factors driving its popularity and influence through the decades:

Independent media-driven. Frankly, I was shocked when I first learned that a media created this program. It may seem counterintuitive today given the relative cost of construction and financial woes of media businesses. However, an independent media is also best positioned to spread the word about the program, attract top talent, and interested audience. And an independent media has the trust necessary for an unbiased assessment of results after the projects were built, a trust that is rarely achievable with self-initiated commercial promotions by construction companies or developers.

Outstanding architects. The Case Study Houses program attracted influential contemporary designers like Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames allowing them to express their solutions freely.

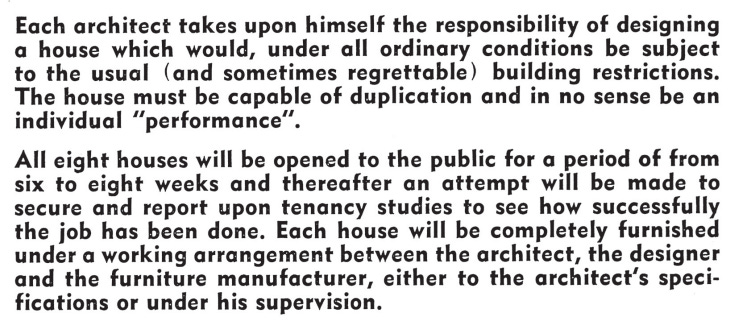

Practical, scalable, open-sourced designs. While given creative freedom, architects had to design projects within reasonable constraints of local regulations, available materials, and a budget attainable for a middle-class family of the time. It was not an exercise in pure artistic expression, but a practical exploration of new housing possibilities.

Constructed in real life. Most of the projects designed within the program were actually built. The act of implementing new proposals and ideas in physical form with all regulatory and construction constraints was a necessary proof point for “Post-War” design. These weren’t just “dreams”, they were real, tangible structures.

Ability for many people to experience them first hand. The program was designed to allow readers of the magazine and the general public to tour the houses after they were built. Over the years, the houses attracted over 350,000 visitors to experience them firsthand. This direct interaction with the innovative designs left lasting impressions on many, including professionals and enthusiasts alike.

These five aspects of the program may seem trivial and common sense, but combining all of them was imperative for its lasting success. Remove one, and something important would be missing.

Modern precedents

Most modern precedents aimed at promoting innovative building solutions and new construction technologies are examples of combining some, but not all, of the above approaches. While producing helpful and well-meaning results, they often fall short of achieving the same level of influence and longevity as the Case Study Houses program.

Architecture competitions

Architecture competitions are great for generating innovative ideas and designs. However, they often lack the crucial element of actual construction.

For example, Los Angeles held a series of local design competitions like Low-Rise: Housing Ideas for Los Angeles design challenge in 2019 or Los Angeles Affordable Housing Challenge. While these ideas may have produced thoughtful concepts, the absence of built examples limited their real-world impact.

The Los Angeles ADU Standard Plan Program, arguably, took this much further than an ordinary competition by pre-permitting selected designs on a city level. That means that a homeowner interested in applying these designs would be certain that it complies with building department requirements, reducing some of the headaches and uncertainty that comes with new construction.

The problem is that these ADU designs have not been built as part of the program. Local residents, investors, and developers couldn't fully experience what these designs would feel like. And more importantly, they didn't provide a reliable basis for their construction cost.

Expos

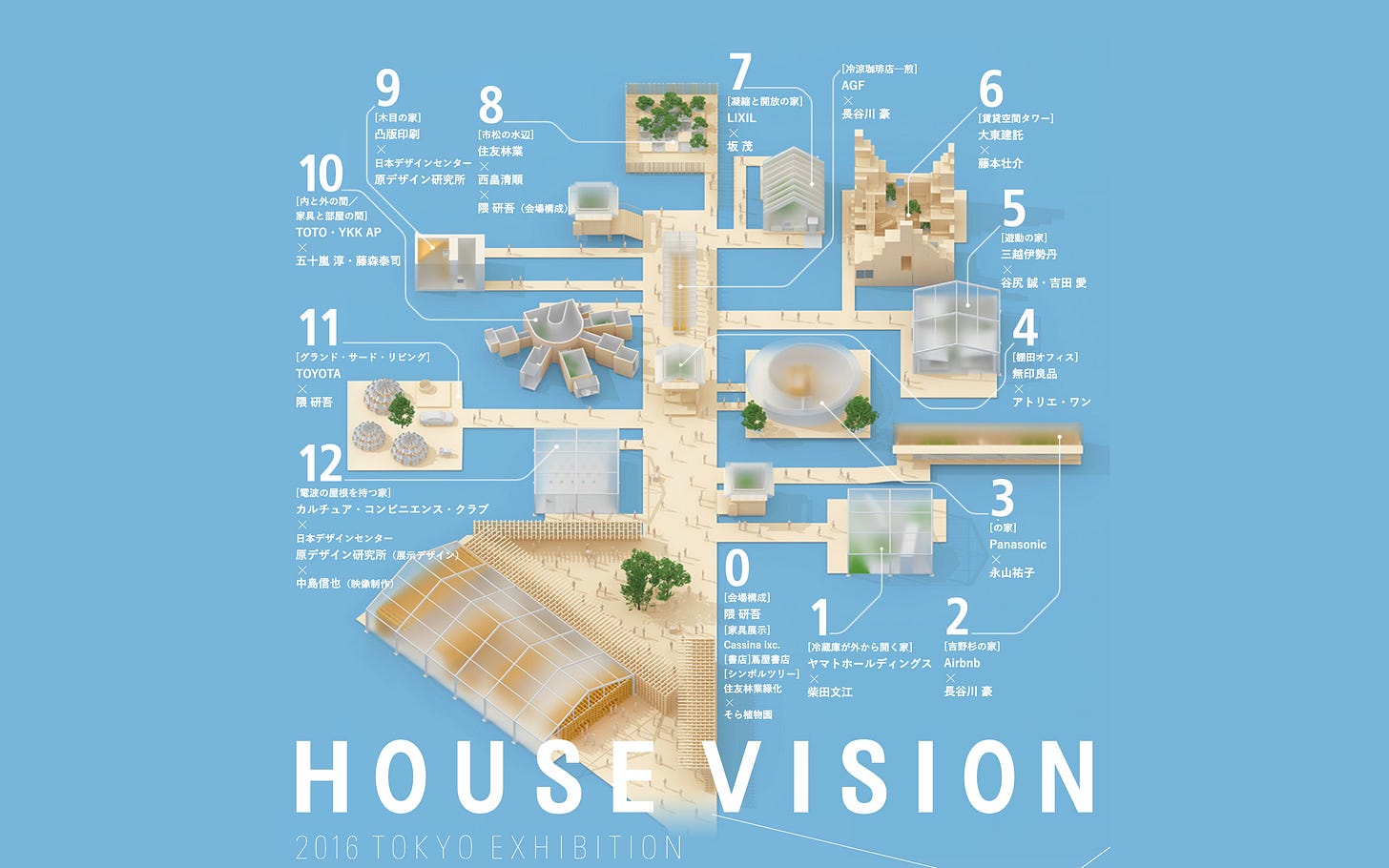

Expositions combine elements of design excellence, real-world construction, and public accessibility.

One of my favorite expo example is House Vision in Japan: the project brought together architects, designers, and companies to create full-scale house prototypes that addressed contemporary living challenges.

Expos are great for inspiration, getting many people to experience spaces first hand, and yet they are lacking in some critical ways:

Temporary nature: Unlike the Case Study Houses, which became permanent residences, most expo prototypes are typically dismantled after the exhibition.

Less emphasis on replicability: While the Case Study Houses aimed to provide practical, buildable designs for middle-class families, Expo prototypes are often more conceptual and less immediately applicable to mass housing.

Hospitality experiments

Among some of the rare exampes of concept houses having a life after the Expo is Yoshino Cedar House that was created by Airbnb Samara and transported to the region that produced the wood it was made of. The project remained as a short-term rental managed by the local community. This allowed visitors to experience it first hand long past the Expo closure.

Hospitality experiments allow to come close to replicating the success of the Case Study House program and, in some ways, surpass it by allowing more people not just to tour the places but to call them home, even if only for a few days.

I've been rather skeptical of 3D printing as a viable solution for housing. At the same time, I see hospitality as a perfect medium to allow for unrestricted experimentation with its potential. And I wouldn’t mind being proved wrong.

For example, Icon3D has partnered with El Cosmico to develop a 60 acre masterplanned community in Marfa, TX that combines 3d printed houses for sale and a 3d printed hotel. It's an ambitious endeavor that shows a wide range of designs and configurations that takes full advantage of the technology and allows guests from around the world to experience it firsthand.

In a similar spirit, Airbnb has established its first $10 million OMG! Fund and sponsored 100 hosts around the word to implement their unique (and often odd) concepts.

Hospitality projects like Living Architecture (UK) or Not a Hotel (Japan) have been collaborating with leading architects on experimental projects and renting them out for anyone to experience them.

Hospitality shines with unique designs. Unfortunately, it’s less effective when it comes to projects that are meant to be more pragmatic and repeatable, limiting its impact on the broader housing industry.

Venture startups

In the past decade, venture capital became one of the leading financial drivers for experimental construction and prototyping. Although it may not always be the best long-term fit for real estate innovation, construction startups created new housing products to various degrees of success.

Just like Case Study program, venture startups’ ambition is to propose scalable models that could be replicated widely. And similarly to the Case Study Houses Program, venture startups are generally media magnets, and their media coverage is typically disproportionate to the actual volume of units delivered.

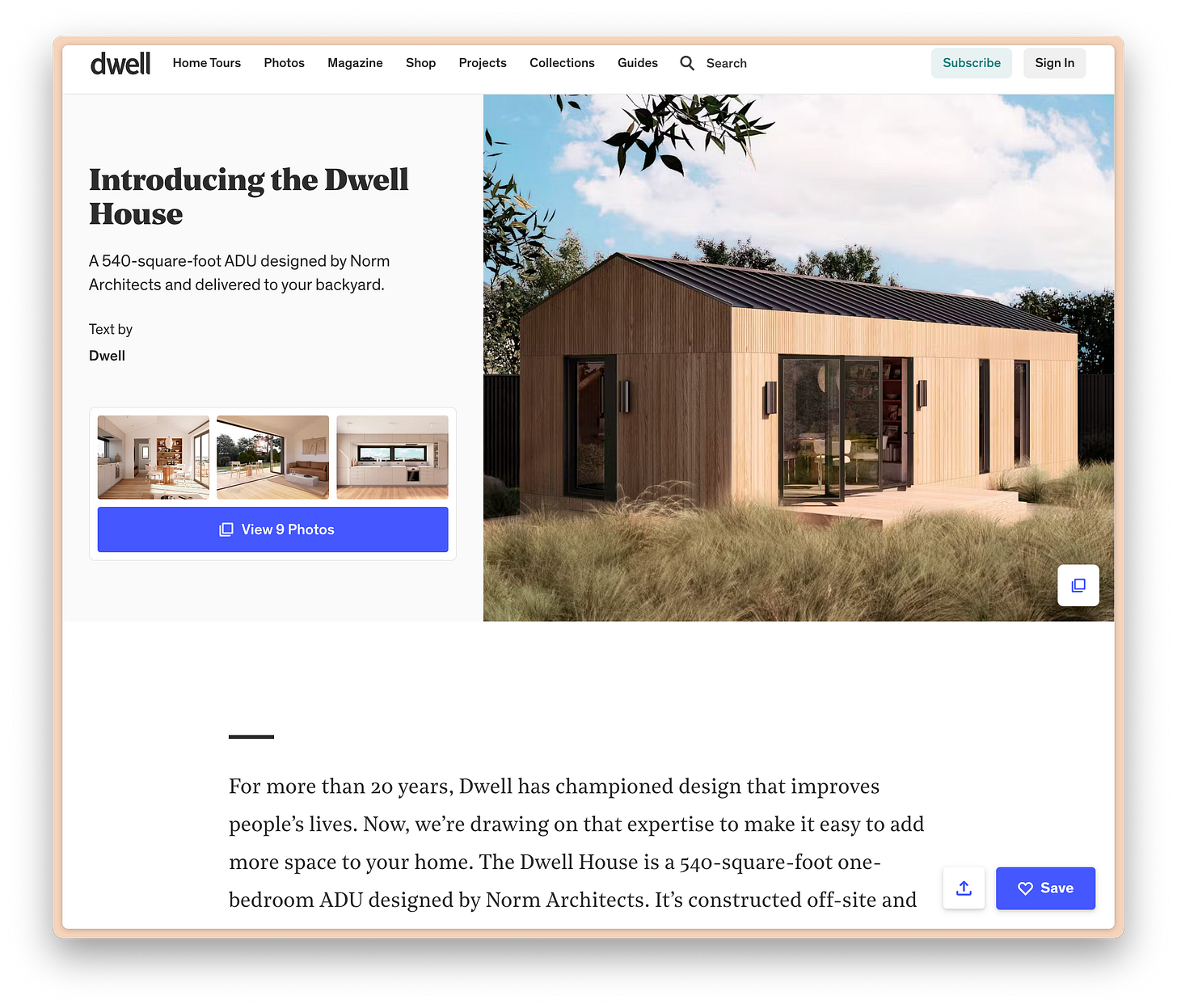

One of the closest modern example echoing the Program is Dwell’s partnership with Norm Architects and Abodu in designing their own “Dwell House” that they promoted in their own media outlet.

Where venture experiments depart from the ethos of the Case Study program is their proprietary nature. Most startups seek to control their designs and technology betting on scaling them and gaining market share. The Case Study program fully open-sourced their designs and findings to spread the precedents throughout the country.

Here we have to acknowledge that the Case Study program existed in a vastly simpler regulatory context. Today, zoning codes are far more granular and complex and building codes vary throughout the U.S., making any open source designs far less likely to be spread.

However, companies like DEN prove that it, in fact, may be possible. And projects like Culdesac act as a viable proof point for other developers considering car-free communities across the country.

How could a Case Study Houses 2.0. program look like?

This brings us to the final question. How could a modern equivalent of the Case House Program look like?

Naturally, it would follow similar traits to the original program: it would need to be media-driven, focus on practical and scalable designs, involve best design teams from around the world, must be constructed in real life, open to a wide audience, and open source its designs and post-occupancy analytics.

I think that it could work as a media-driven real estate revolving fund that would finance both a design competition and construction, run it as an expo and hospitality operation for a few years, and later refinance or sell each project, using the proceeds to finance new projects. Rinse and repeat.

The projects can showcase innovative responses to emerging legislation or constraints, new construction technologies, and test new concepts of modern living. Unlike the Case Study Program, it would be important to go beyond the form factor of a single family home and experiment with products that have more density.

Where building a full-scale multifamily or commercial prototype would not be economically or technologically feasible, an analogous approach to ETH's DFAB house can be implemented: introducing multiple concepts within the same building structural frame.

With so many challenges and opportunities in the built environment, this would be an exciting time for a modern reboot of the Case Study Houses program. And who knows, maybe it could inspire a generation of designers a century from now, just like the original Case Study Houses do.

— Fed

Great take that Architecture without actual construction is halfway, and real experiments should be done on a full life cycle. Even for Architectural study programs, this would be revolutionary.

Though not nearly as impressive as this program from decades ago, some building departments (like San Jose, CA) have worked with architects to streamline ADU development with pre-approved designs that fit most backyards. It would be incredible to see an ADU catalog - at least as a start - to move the needle of starts to completed builds in other parts of the country.