Missing Middle Capital For Real Estate Innovation

Designing a new capital product that sits between traditional real estate equity and venture capital.

Venture capital is often not the best way to finance innovation in real estate development and operations. Especially, for projects that involve the physical world. Permitting, construction timelines, and labor-intensive operations limit the ability to scale rapidly. At the same time, relatively slim margins make it more difficult to cover the costs of maintaining a large team optimized for growth.

I call this an open secret because whenever I meet fellow founders in the industry, the conversation inevitably leads to someone saying, “Venture is a tough match for real estate.” It’s a secret nonetheless because publicly acknowledging this sentiment might reclassify a company in the eyes of investors from a growth business to a traditional real estate operation, undermining its ability to raise funding for innovation.

There is a need and an opportunity for a new capital product that is more risk-tolerant than traditional real estate equity, but less growth-demanding than venture capital.

This topic is personal for me. When I worked on prefab housing at Airbnb Samara, I witnessed firsthand how difficult it is to reconcile hardware timelines with a software-based organization (eventually, the project spun off into an independent company). When Petr and I started Apt with the aim of standardizing and streamlining the development of low-rise multifamily, we believed that we could achieve development at a venture-like pace. However, we quickly discovered that our in-house software automations were hindered by per-project permitting and customization requirements, making it more akin to a traditional developer than a startup. Since these experiences, I have been constantly thinking about ways to better align the pace of real estate innovation with appropriate funding.

In this article we’ll explore:

The binary nature of funding options for real estate endeavors;

The reasons why venture capital may not always be the right fit for innovation in real estate;

How venture dollars may undermine OpCo-PropCo arrangements;

Concepts for “Middle” capital products and the size of the opportunity.

The Procrustean Bed of Capital Choices

Imagine a risk and growth gradient for individual real estate investment opportunities. On the one extreme, we would place a ground lease in a prime location that promises a steady, tax-optimized cash flow. On the other extreme, we would place something like Airbnb — a ridiculously risky bet that now operates more units than Marriott, Hilton, and other legacy hotel chains combined.

In the middle of the spectrum, we would find innovative businesses constrained by the physical environment. For example, developers using new construction technologies, new untested amenities, property managers and co-living operators, experimental industrial and manufacturing operations, alternative hospitality developers, and other “Middle projects”.

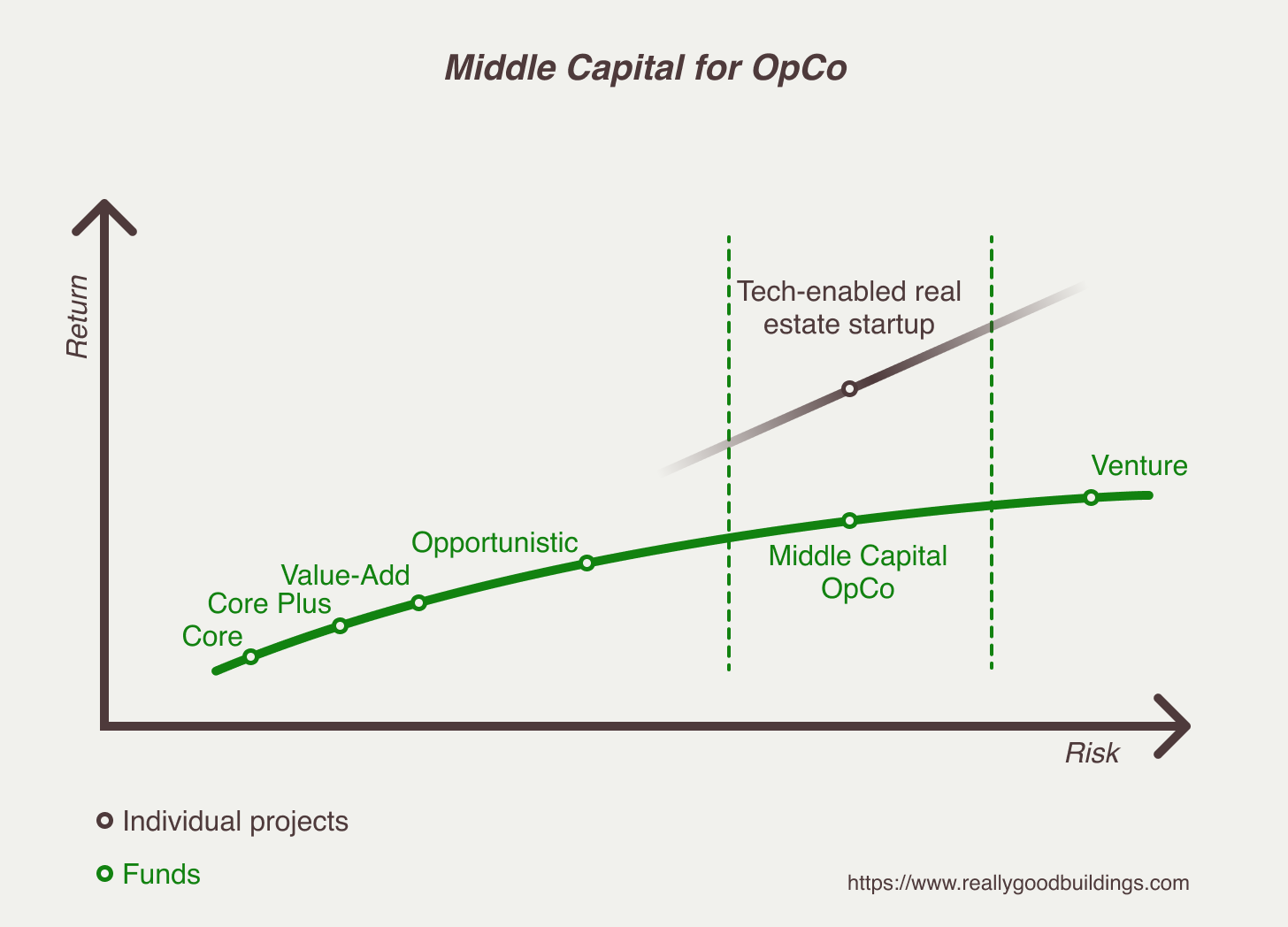

Capital products1 available for financing real estate projects are not distributed evenly across the risk/return spectrum. Instead, they are concentrated towards the tails of the spectrum.

This results from the conceptual and economic differences between traditional real estate and venture investing. Real estate capital tends to be risk-averse, optimized for tax and cash flow, and often requires extensive track records and personal guarantees. By contrast, venture capital is risk-tolerant, welcoming newcomers with no strings attached but expecting rapid expansion and go-big-or-go-home outcomes.

These distant capital options create a “procrustean bed” for early stage real estate projects who fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. This creates two distinct challenges:

Some of the Middle projects end up in the traditional real estate capital bucket and either don’t get funded at all (due to being perceived as too risky), or have to abandon their novel ideas and become a traditional operation.

Other innovative Middle projects try to qualify for the venture track. Many succeed in attracting early stage funding, but fail to meet investors’ growth expectations over time.

The second problem became apparent with the first generation of tech-enabled real estate developers and operators, such as WeWork and Sonder. These companies tied up venture capital in real estate leases and built large organizations optimized for growth. However, they ultimately fell victim to mismatched capital placement and the gap between investor expectations and their core business profitability. As MetaProp, one of the prominent proptech venture funds, puts it:

“In the last decade, a staggering amount has been deployed into tech-enabled real estate businesses such as WeWork, Sonder, and Opendoor, which manage and operate physical real estate. How should these businesses be categorized? Are they merely old-fashioned real estate businesses in a shiny new candy wrapper, or is there something new and innovative about how they operate? These companies seek to leverage technology in various parts of their business, streamline manual processes, and focus on user experience to surpass traditional real estate returns <...>

These startups raised a bulk of their capital from venture investors that have historically financed high-growth, high-margin software businesses and have the highest return expectations. This puts moderate-growth and capital-intensive tech-enabled real estate companies in a tough position when they receive capital from similar investors on similar terms.

In response to the inefficient use of venture capital in real estate applications, the industry has been shifting towards adopting the OpCo-PropCo model (short for “operating company”, “property company”). It’s an arranged marriage of sorts between venture capital backing the OpCo, which holds all intellectual property, and real estate equity and debt capitalizing the PropCo, which holds specific properties and leases. You can learn more about how this approach works here.

Venture-Backed OpCo-PropCo Isn’t a Panacea

OpCo-PropCo is a time-tested structure and is a massive improvement over locking up venture capital in real estate assets. Most established hospitality operators have adopted it years ago. For example, companies like Hilton have split their business between an operating company (Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc.) and a real estate investment trust (Park Hotels & Resorts Inc.) in charge of development and asset management. A more recent example is LifeHouse, a hospitality startup that has raised venture capital for its OpCo (brand, design, and software development) and now manages over hundreds of millions in real estate assets capitalized in a traditional way. Similarly, Wander, a short-term rental startup, has launched its own REIT to finance expansion.

OpCo-PropCo funding is currently the hottest topic among proptech venture investors. The number of OpCo-PropCo funds has been growing over the years, and many renowned founders and operators are considering their next move in that space.

However, there may still be trouble ahead:

As long as the OpCo is funded with venture dollars, it will be expected to grow at a venture pace. Unfortunately, this may not be feasible for many Middle businesses dealing with custom entitlements, permitting, and bespoke construction for each individual project. Cheaper property-level capital can help in many ways, but it doesn’t solve policy and physical delays. Personally, I anticipate that a significant number of venture funded operating companies will undermine investor expectations within the next few years.

To address this issue, we can introduce capital products tailored for the middle of the risk-return real estate spectrum. Specifically, let’s explore:

OpCo-side Middle capital. An early stage fund that promises venture-light returns on the portfolio level while expecting relatively lower growth (and lower failure rate) from each individual company.

PropCo-side Middle capital. A co-GP fund for property-oriented investments that secures warrants in brand- and tech-enabled operating companies to compensate for the higher risk.

Middle Capital for Operating Companies

It may be possible to introduce a new type of early-stage OpCo fund that could achieve similar fund-level returns to venture capital, while having relatively lower growth expectations for individual companies in the portfolio.

At first, this may sound impossible, but let’s consider the relative benefits of tech-enabled or brand-enabled real estate. While it may be slower than some tech startups, it also carries a lower risk of going to zero.

These characteristics of tech-enabled real estate projects make it possible to structure a portfolio of companies that promises investors similar returns to venture funds. The lower delinquency rate in the portfolio may balance out the relatively lower potential for high returns from the winners.

Venture Company vs. Venture Fund

The general public tends to discuss venture capital through the lens of individual companies, especially the rare winners that make staggering 100x-1000x returns.

However, far less discussed is the fact that, on a fund level, venture returns tend to be more modest. Good venture funds return approximately 3x on their investors’ equity, but average performance can often be as low as 0.5x (50% loss) to 1x.

This is due to the extremely risky profile of the individual venture investments. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 45% of new businesses during the first five years, and 65% during the first 10 years. These statistics have been fairly consistent since the 1990s.

The structure of a venture fund requires each individual company to have the potential to yield returns that can cover the entire fund. As a result, venture is a tough match for real estate projects, even when considering only the OpCo side.

Middle Portfolio

Now, consider an alternative scenario where an investment portfolio consists of innovative real estate projects that may yield less than 10x but have a much lower failure rate than 50%-65%. Such a fund may ultimately deliver the same 3x return to its limited partners, possibly with even better reliability than venture funds.

Why do I believe that a portfolio with a relatively lower failure rate is a viable option?

The commercial real estate industry has a delinquency rate of under 1%. Even following the crisis of 2008, its failure rate stayed below 10%. However, due to Covid, the hospitality industry saw up to a 15% failure rate on commercial real estate loans.

The gap between the highest commercial delinquency rate (10%-15%) and the failure rates of startups (45%-65%) is massive. Innovative real estate projects may increase the risk and returns volatility compared to the traditional commercial real estate, but still be safer than pure venture. Most of the time, they have fallback options to revert to traditional operation.

Rather than focusing on the limitations of tech-enabled real estate businesses, it is time to embrace their unique benefits. A Middle OpCo fund could structure its portfolio to assume a failure rate of 15-30%, while also participating in the upside potential of successful companies.

Tax efficiency is a subtle yet important factor to consider when deciding on the structure of venture-funded OpCos for Middle real estate projects. Most large developers are structured as pass-through legal entities, such as limited partnerships or limited liability companies. This allows owners and investors to write off some of the paper depreciation losses from a building against other income, reducing their overall tax bill. In contrast, venture capital typically requires operating companies to be registered as Delaware C Corporations, which do not allow for pass-through taxation.

A Middle Capital OpCo fund could operate similarly to private equity search funds that offer co-investments to real estate general partners to support emerging operators. Rather than partnering on a specific property or joint venture, these funds take a stake in the long-term future of an emerging real estate firm. This structure may be optimal for supporting incremental innovation in real estate development.

An important precedent in this space is Almanac Realty Investors (now part of Neuberger Berman), which has invested over $7 billion into 51 real estate operating companies over the past several decades, including major players like RXR.

Middle Capital for Property Companies

On the property side, a Middle PropCo fund offering would take the next logical step after the opportunistic funds. In fact, it may as well be called “Opportunistic Plus” because it would remain closer to real estate than to venture.

An important difference is that typical opportunistic funds invest in individual projects and properties, while the venture funds invest in their parent operating organizations.

Opportunistic real estate capital already takes risks on entitlement and construction. More radical and innovative projects would add new technological or business model risks. To compensate for this added risk, a Middle PropCo fund would need to participate in the upside of the parent company (OpCo) beyond a specific property deal.

At the same time, having exposure to asset ownership or the ability to save a risky bet by reverting to a more traditional real estate approach can reduce the downside compared to a pure venture investment.

The Middle PropCo approach is gaining more attention and experimentation. Jonathan Wasserstrum, founder and chairman at SquareFoot and a prolific proptech angel investor, is currently working on a Middle PropCo capital solution. He provides relatively affordable and risk-tolerant co-GP capital for innovative real estate property investments, such as dark kitchens, SB9 developers, co-equity startups, branded student housing, etc. To compensate for the relatively higher risk compared to a traditional real estate deal, Jonathan uses warrant coverage in the operating company.

Overall, Middle OpCo and PropCo funds could contribute to a very healthy menu of capital options for startup operators:

OpCo Funded Solely Through PropCo Management Fees

In some rare cases, a large early-stage PropCo investment can make a separate fundraising for OpCo irrelevant. For instance, a data-driven Single Family Home investment and management platform Amherst was funded with a $200M “seed raise” of a new fund. The management fees from the fund were enough to support an in-house data analytics team. If this was a venture backed operation, it would have required a dedicated OpCo raise to assemble the analytics department.

Similarly, CitizenM has grown a new global hospitality brand through a well capitalized holding company and even developed their own software products for guests. All without raising venture capital.

Capital for Innovation as a Time Machine

This leads to a logical question: is funding for innovation in real estate necessary at all? Or should everyone just bootstrap these businesses instead?

Historically, venture funding was not essential to build a massive real estate company. The majority of the largest developers in the U.S. are privately owned limited partnership and limited liability corporations (Related LP, Greystar LLC, Hines LP, Tishman Speyer LP ) that never raised venture capital.

If you spend any time on real estate Twitter, you’ll know that many operators take pride in bootstrapping their fortunes while maintaining 100% ownership. Building a “sweaty” startup is formidable and hard work. While it may be a great strategy for building and preserving wealth, it can also result in a massive negative externality of delayed innovation.

If everyone who has an innovative idea would be required to toil away for 10+ years to accumulate enough resources to invest in R&D and test it by themselves, they may be too late or society may benefit much later than it could.

Early stage capital works like a time machine, enabling people and organizations to build new and better solutions faster. It can save years, and sometimes decades. This is especially helpful for those who lack resources, such as affluent family and friends, or connections to large investment companies.

Real estate imposes a speed limit on this “time machine”. Zoning constraints, lengthy entitlement timelines, and restrictions on new construction methods all contribute to a slower pace of growth and innovation adoption. While this may make venture capital a difficult match for real estate, the industry still requires appropriate funding for R&D and experimentation. Middle Capital can become a crucial complement to venture capital in promoting innovation in this industry.

Sizing The Middle Market Opportunity

It's difficult to determine how many organizations fall within our target zone of middle innovation. How many qualified for the venture track? How many had to become traditional real estate organizations? How many chose not to start at all due to the lack of compatible capital? And how many would start if the capital became available?

Skeptical Scenario

The pessimistic view is that the distribution is naturally skewed towards the extremes, and that only a minority of existing or potential projects lack Middle capital funding.

Aleks Gampel, founder of Cuby Technologies, expressed concern that finding compatible, high-quality operators in the market may be prohibitively difficult: “there is simply not enough LifeHouses out there”.

Optimistic Scenario

A more positive argument would be that there are many “invisible” Middle companies that are currently hidden in either the traditional real estate or venture buckets. Moreover, there are many companies that have never received any funding at all (I will spare you the stereotypical image of a WWII plane with bullet holes.)

The optimistic scenario is backed by many conversations I've had over the years with developers working on relatively novel projects, as well as with tech-enabled real estate startup founders. Developers state that it is very difficult (if not impossible) to find equity partners willing to support new approaches, and tech founders worry that they may struggle to secure follow-on funding due to the comparatively slow pace of growth.

There may be many candidates for Middle funding:

Companies taking advantage of local policy changes like ADU and SB9 developers and prefab sellers;

Branded operators of new retail and professional services with physical storefronts (primary care, dentists, veterinary clinics, etc);

Industrial co-manufacturers;

Dark kitchens;

Tech-enabled developers;

New charter school operators;

Niche co-living, co-working operators, and tech-enabled property managers;

New operators blending hospitality and residential or experimenting with rent-to-own vehicles.

and many more…

Venture capital will still be critically important to finance deep tech innovation in real estate like construction robotics, material science, augmented reality, manufacturing, prefabrication, and other complex research and development initiatives.

However, according to Bryce Roberts of Indie.vc, only 1% of new companies use venture capital. It’s no surprise that there may be an underserved niche in the market between traditional real estate equity and venture funding.

Real estate debt and equity is the largest asset class in the world, so it makes sense that it can support its native way to finance innovation without relying solely on venture capital optimized for software and hard tech. In fact, a similar narrative is emerging with "calm funding" for bootstrapped software companies.

I would bet that within the next 5-10 years, more money will be invested in innovative real estate businesses through new types of Middle Capital vehicles than through traditional venture capital.

Time will tell. For now, let’s get back to building.

Thank you for reading,

— Fed

This article is for education and entertainment purposes only, no offer is being made to buy or sell securities.

Further Reading

Venture Growth Expectations vs. Real Estate

“Startup=Growth” by Paul Graham

“Real Estate Lacks Network Effects, And I’m Ok With It” by Moses Kagan

OpCo-PropCo

“OpCo-PropCo Primer” by Kunal Lanawat of Agaya Ventures

“OpCo-PropCo Evolution” by Kurt Ramirez of Nine Four Ventures

“Intelligently Financing Tech-Enabled Real Estate Concepts” by MetaProp

“The Big List of OpCo-PropCo Investors” by Brad Hargreaves of Thesis Driven

“The Future of OpCo-PropCo Model” by Brad Hargreaves of Thesis Driven

Emerging Alternatives to Venture Capital

“The Calm Capitalists” by Mario Gabriele of The Generalist

“Venture Capital Is Ripe for Disruption” by Evan Armstrong for Napkin Math

“We’re Selling Entrepreneurship Short” by Bryce Roberts

“Venture Capital Risk and Return Matrix” by Industry Ventures

“How Venture Capital Works” by Harvard Business Review

Footnote. Real estate investment/fund types:

Core: The most conservative blend of risk and return in the private real estate segment. Core properties tend to be built exceptionally well, located in great areas, and burdened by very few deferred maintenance requirements.

Core plus: Properties that have some minor issues or are not fully leased but are still considered to be in good locations and have the potential for stable income streams.

Value add: Properties that require significant improvements or renovations to increase their value and income potential, but promise higher potential returns.

Opportunistic: Distressed, underperforming, or new construction. These opportunities have higher risk and potential for higher returns compared to the above categories.

👏

brilliant observations & analysis.

seems like there's a blended model that can combine the risk / growth of VC with the asset value / liquidity of RE to make a product that is better than the sum of the parts.

would be fun to chat more about this sometime...